Eva Sakuma’s exhibition Forgotten Preciosness (or «Zapomenutá Vzácnost») at Praguekabinet was opened on October, 17. The night before, I was desperately looking for my copy of Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space all around my apartment.

The reason: I needed something to help my vocabulary to say more about spaces and places, and it seemed that Bachelard was the one to give me the words I needed. Frankly, Foucault (heterotopias, my favourite subject of all times) and Georges Perec would be more useful in this aspect, or urbanism, for example, (the part where people disappear from the cityscape so that the city can be seen better), or Tanizaki’s In Praise of the Shadow, which, with a little help of Okakura Kakuzō, could describe absolutely everything, because the art we’re going to discuss below contains a lot of Japanese elements, and Japan is a favourite topic here.

I remembered all of it during my search, and when Bachelard’ book was finally discovered in the most prominent place (of course, where else could it be?), it looked absolutely unnecessary. And it was even more unnecessary, because I was interested in image, and the book focused on literature.

But in the end I was digging in the right direction. Because I felt that I needed to remember the experience of reading and interacting with a literary work, so, in a very, let’s say, distorted form Bachelard’s book became very useful anyway.

This time I was lucky enough to visit the opening of the exhibition (no formal speech, just a silent description on a piece of paper, but lots of public and a lot of Fornasetti porcelain, because the gallery specializes in it), and I got a book with an autograph. We all know how much I love books, so for me it was another what’s-not-to-like evening.

Forgotten Preciosness shows not only previously non-exhibited works that left the studio for the first time (by the way, Eva Sakuma’s exhibitions take place every two years at Praguekabinet, recently with the participation of the same curator — Ela Suárez Illerias), but also a communication between nature and a cityscape. Not in a form of a dialog, but in a way of co-existing.

Of course, the cityscape is not Prague. Prague can’t give us such a contrast, it is smaller than the grey metropolis of the background. It’s more like the city where I lived before. The city of huge multi-story buildings made up of tiny apartment cells and hours-long traffic jams, the city with an official population of five million, who for some reason eat like seven and a half.

It’s more like New York (such familiar architecture…), but of course, it’s a very Japanese city, with all this glass, and balconies, and stairs, and roads… Why not? If everything else is Japanese here?

The Japanese setting prevails, and there is no one but a woman (historically, she is considered closer to nature, so such stereotypes are also handy, if there is no other version of the artist’s choice, but A Room of One’s Own is also an option), she turned her back and we can not see her face, which also gives us the theme of loneliness (or not: we do not need anyone else, we communicate with nature and all types of spaces on our own, our perception of the surrounding world is individual, it’s easier to take a breath and to think when no one bothers you… et cetera).

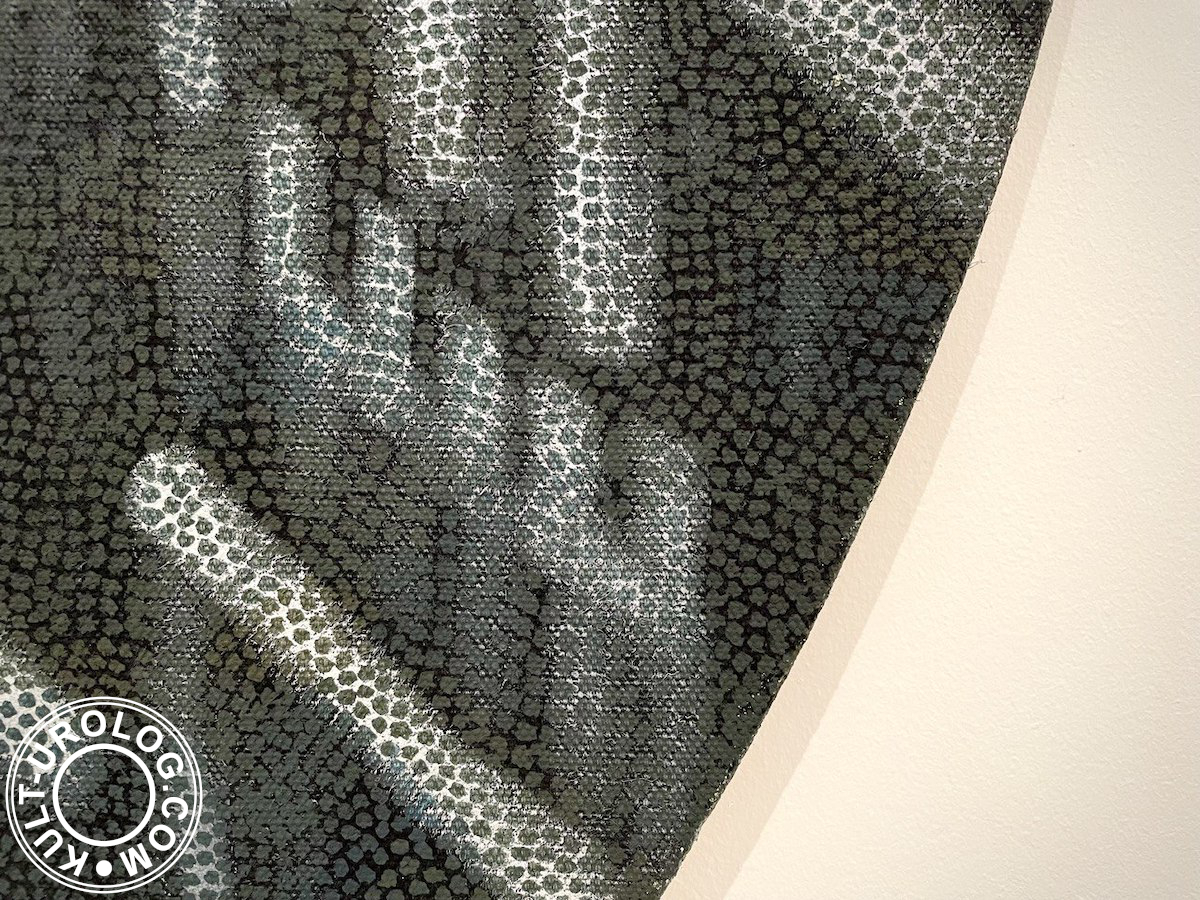

It’s all about layers, like in Japanese clothing or music (and this also applies to the texture of the canvas), and this technique is common to most of Eva Sakuma’s works (at least, the ones I’ve already seen). There is definitely a more important object in the picture, but we seem to be looking at it through the glass that reflects something else. That’s how interior turns to forest (here, just because we can, we also gonna mention the relationship of traditional Japanese house’s space and the surrounding nature, and, yes, we do mention it).

In this case nature and cityscape not only interpenetrate, overlap, cover each other and create new layers (transparent layers, and they don’t mix — that’s important), but nature seems to win. And the city is not a reflection, but a primer.

The grey city, like a black and white photograph, serves as a contrast and a backdrop to the green and brown tones of what we consider to be the natural environment: bonsai, rock garden, moss… This is nature, but not wild, it is reinvented by man — another sign of civilization.

Although even if we think so, it is not necessarily true in reality.

Nature only seems tamed and understandable (people are very self-confident in this regard), but is it really so? Bonsai in a pot is still a tree, with its own rhythms and relationships with the world around it, gravel and specially placed stones in the garden are still stones (rather wild, even being processed), moss, which is carefully looked after and forbidden to walk on, it still has a mind of its own (well… sort of). And what do we know about them? Do they belong to civilization for real? Do we really own them? And, yes, I could bring in Kant here, but, nope, I know when to stop.

Another sign of nature’s victory is daylight. Not like Hammershøi’s smooth glow of the North (it’s hard not to think of Hammershøi, I don’t know why), but transitions and reflections of light, contrasts, shadows and darkness that exist due to light, and therefore light is everywhere, and we don’t need any philosophy there, because physics is enough.

And this is the moment, when we finally take our Bachelard out, because what interests us here is not the text and symbols that usually see in any work of art people who have read a lot of semiotics, but the image itself. We need it to explain what happens when we read, because that’s how I perceive Eva Sakuma’s works.

It’s not about what we see, but about how we see (at least, some of us).

When we read, it’s not just words we communicate to, we always have also a picture (again, at least, some of us). We look through walls, we create a ghostly space around us that can be more real than our entire environment (though it’s also more than visible and fully present), the walls become permeable, the boundary between times is erased, we visualize, we construct scenery and change the light.

It depends on the book, but sometimes one good metaphor worth reading the whole piece (and that’s why sometimes poetry is better), and we are watching our own movie (or static images, it depends) thanks to a couple of words happily married together.

The space around us becomes many spaces. They do not even have to exist, although they may resemble real ones. That’s what we call imagination. That’s why I love the unsaid.

Now we can switch to the previous mode, where the image becomes text again, to say that there is only one work of art, but there are many texts — an absolutely stunning statement (not mine, unfortunately) that allows to write whatever comes to mind and look smarter, even if you don’t understand anything. So, even if the description of the exhibition can be quite specific, telling what the author really wanted to say (or what the curator invites us to notice), everyone anyway is free to see what he is able to see with all his personal experience.

The Forgotten Preciosness will last only till November, 15. All paintings are for sale, and certain are already reserved, but, luckily, none of it has been taken away yet, so hurry up, my little readership, hurry up. This is a nice opportunity to visit Praguekabinet (and don’t miss Fornasetti!), to read your own texts and to tell me that without any Bachelard it also works perfectly.